Ink

“Do not imagine that art or anything else is other than high magic! - is a system of holy hieroglyph. The artist, the initiate, thus frames his mysteries. The rest of the world scoff, or seek to understand, or pretend to understand; some few obtain the truth.”

― Aleister Crowley, The Drug and Other Stories

There is something inherently magical about the act of making art. Crowley summed up elegantly what is ultimately an act of creating something from nothing, bringing an intangible idea into material form, something typically reserved as the domain of the gods alone.

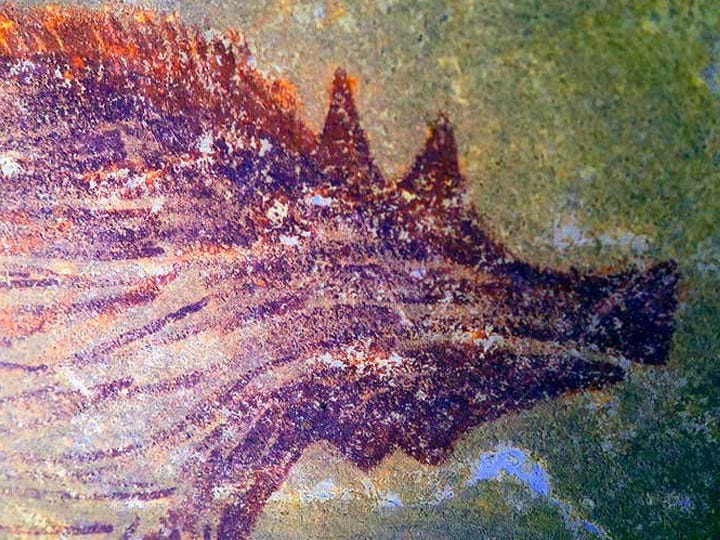

Evidence shows humans and our close cousins have been creating representative art for at least 44,000 years. Cave paintings in Indonesia picture a hunting scene, clearly indicative of figurative thought, and most likely for ritual purposes. If we drop the requirement of narrative, we see our ancestors creating rhythmic marks on a shell at a time depth of 540,000 years, over half a million years before present. It seems that the act of creation has been with us from the dawn of our species. Interestingly, it seems that the materia for making art may have predated the representative art itself, by a long shot. Evidence for human production and use of ochre dates back to at least 300,000 years ago. Ochre is a pigment created from stone high in iron content. From a magical standpoint, iron corresponds with the fiery and creative energy of Mars. It does not come as much of a surprise that at the dawn of our species, we were already harnessing the powers of force and creation. According to Liber 777, the magical power that corresponds to Mars is the Vision of Power. Like the bursting forth of life in the spring, our ancestors took upon themselves the power of gods to create something from nothing.

Fast forward a few hundred thousand years from the time of the first ochre production in Africa, the ancient Egyptians were still using ochre, amongst other pigments, to imbue their art with color and life. By this time, humans had refined their use of art to the highly symbolic transmission of idea: the written word. Hieroglyphs were used as a way to convey ideas and to cement them in the material world with their physicality. Łukasz Byrski writes in his paper Identifying the Magical Function of Script in Ancient Cultures ‒ a Comparative Perspective (warning pdf link):

There is no clear-cut line of demarcation between hieroglyphic writing and representational art….there is evidence of the existence of a belief in some potential magical power of hieroglyphs in ancient Egypt. This can be observed both in the Old Kingdom period (c. 2750‒2200 BCE) in the “Pyramid Texts” and in the Middle Kingdom period (c. 2050‒1750 BCE) in the “Coffin Texts,” where signs were deliberately changed graphically to disable their potential force.

Here we see a cultural recognition of the creational aspect of the hieroglyphs. They are treated as potent forces for change on their own, for both good or bad depending on the powers invoked through each individual sign. Art, through pictorial representation of the spoken word, was richly integrated, and often synonymous with magick. By the Hellenistic era (about 300 BCE—250 CE), a thriving trade in magical amulets, scrolls and other objects colored the spiritual landscape. Our best example of magic from this period is the Papyri Graecae Magicae, or PGM (pdf of document).

Despite being called the Greek Magical Papyri, the PGM actually incorporated magical spells, hymns and formulae from Jewish, Egyptian and Graeco-Roman cultures. Amongst the many spells and hymns are constant references to written phrases or images that are necessary for empowering the spell. In one spell for requesting a dream oracle from Besas, the practitioner must mix together ochre, amongst other ingredients to make an ink for writing out words of power. Numerous other spells require myrrh ink. In the paper Single-Stemmed Wormwood, Pinecones and Myrrh, Lynn R. LiDonnici writes:

By far, the most frequently required incense in the PGM corpus is myrrh. Myrrh appears so frequently because it is used in the corpus both as an incense for rituals and as a component of black ink for the writing of ritually important words, charaktêres, or pictures. Many recipes call either for writing "with myrrh," using "myrrh ink," or "myrrhing" a paper, where writing is clearly meant.

Myrrh as a magical ingredient has an interesting list of correspondences. In Liber 777, Myrrh corresponds to key 3, Binah, and secondarily to key 23 and the letter מ. Spelled in Hebrew, Myrrh is מר with the gematria value of 240. This number also corresponds to רמ, a title of Kether meaning the lofty one, elevated. It also corresponds to על פני or “on the face of.” From Genesis 1:2:

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

The waters here are the waters of Binah. Remember that the letter מ embodies the element of water. Thus we can magically link myrrh with the act of creation. If we divide 240 by 3, the number of Binah, we get 80. The Hebrew letter פ has the value of 80, and the attribution of Mars. Here then, myrrh embodies the force of creation in its manifest form.

I think it is easy now to construct a narrative for the continuity of the practice of creating sacred images and words as vectors for magical empowerment. Furthermore, the material we choose can enrich this even further by bringing their own magical correspondences to the mix. For more than half a million years, we as a species have been doing this exact thing: bringing down the fire of creation through our art and our words. I think we can now make the case that the act and result of art is a time honored access point to the divine that is backed up by sound magical reasoning. It seems obvious, really, but often we overlook the basic foundations of what we do and why we do it.

Praxis

To create myrrh ink, burn myrrh over a clean burning coal. Using a metal spoon held cup side down directly over the stream of smoke. Collect as much of the soot as you can. Slowly add a few drops of water into the spoon and mix. Dip a dip pen or brush into the ink to use.

Consider adding astrological timing to the collection and preparation of the ink. The day and hour of Mercury would be an appropriate all purpose choice, though if you would like to harness some of the creative aspects mentioned above, perhaps choosing a Tuesday or Saturday would also be appropriate. If your astrological skills are up to the challenge, you could even consider a more in-depth election, perhaps when Aries is rising. Mix and match as you will, experiment and see what fits best for your needs.